Mechanical ratchet mechanism allows cell division without a closed contractile ring

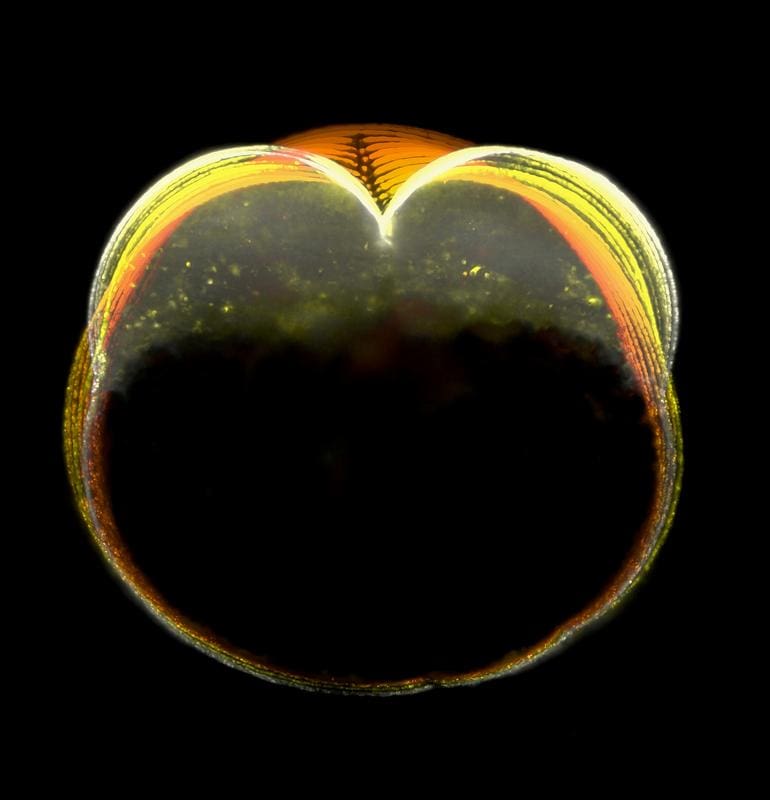

Researchers from the Brugu├®s group at the Physics of Life Cluster of Excellence at the Technical University of Dresden have discovered a new mechanism of cell division. In early embryonic cells of zebrafish, cells divide despite an open, not completely closed contractile ring of actin. This process, known as the mechanical ratchet, calls into question the previous textbook presentation of cytokinesis.

The classic mechanism of cell division is based on a complete, contracting ring of actin and myosin that constricts the cell. In egg-laying species with large, yolk-rich cells ŌĆō such as zebrafish, sharks, birds or reptiles ŌĆō such a ring cannot be closed geometrically due to the cell size and the yolk. Until now, it was unclear how the division will nevertheless take place.

The team studied zebrafish embryos with large, yolk-rich cells and fast cell cycles. Precise laser cuts on the actin ligament showed that the ligament continues to constrict despite the interruption. Anchor points are distributed along the entire band. Microtubules stabilize the band mechanically and signalling.

Disturbances of the microtubules due to depolymerization or physical obstacles led to the collapse of the actin band. In the interphase of the cell cycle, microtubule asters stiffen the cytoplasm and anchor the ligament. In the mitotic phase, the cytoplasm becomes more fluid, which allows constriction.

During the M-phase, the ligament is unstable and partially retracts, but does not collapse completely. The fast cell cycles save this state: In the next interphase, the cytoplasm stiffens again, stabilizes the ligament and enables further constriction in the following liquid phase. This cyclic alternation of stabilization and liquefaction acts like a mechanical ratchet and extends the division over several cell cycles.

The mechanism solves the problem of large cells and fast cycles where a full ring would take too long. The discovery is considered a new paradigm for cytokinesis in yolk-rich embryos and emphasizes the role of dynamic material properties of the cytoplasm.

Original Paper:

A mechanical ratchet drives unilateral cytokinesis | Nature

Editor: X-Press Journalistenb├╝ro GbR

Gender Notice. The personal designations used in this text always refer equally to female, male and diverse persons. Double/triple naming and gendered designations are used for better readability. ected.